6 Questions with Michael Eisner

The former Disney CEO on buying an English football club, bringing a Hollywood blueprint he crafted with Barry Diller to sports, and the time his wife saved him from a bear

Michael Eisner loves camp. Not the Met Gala theme. The actual, bugle-call kind.

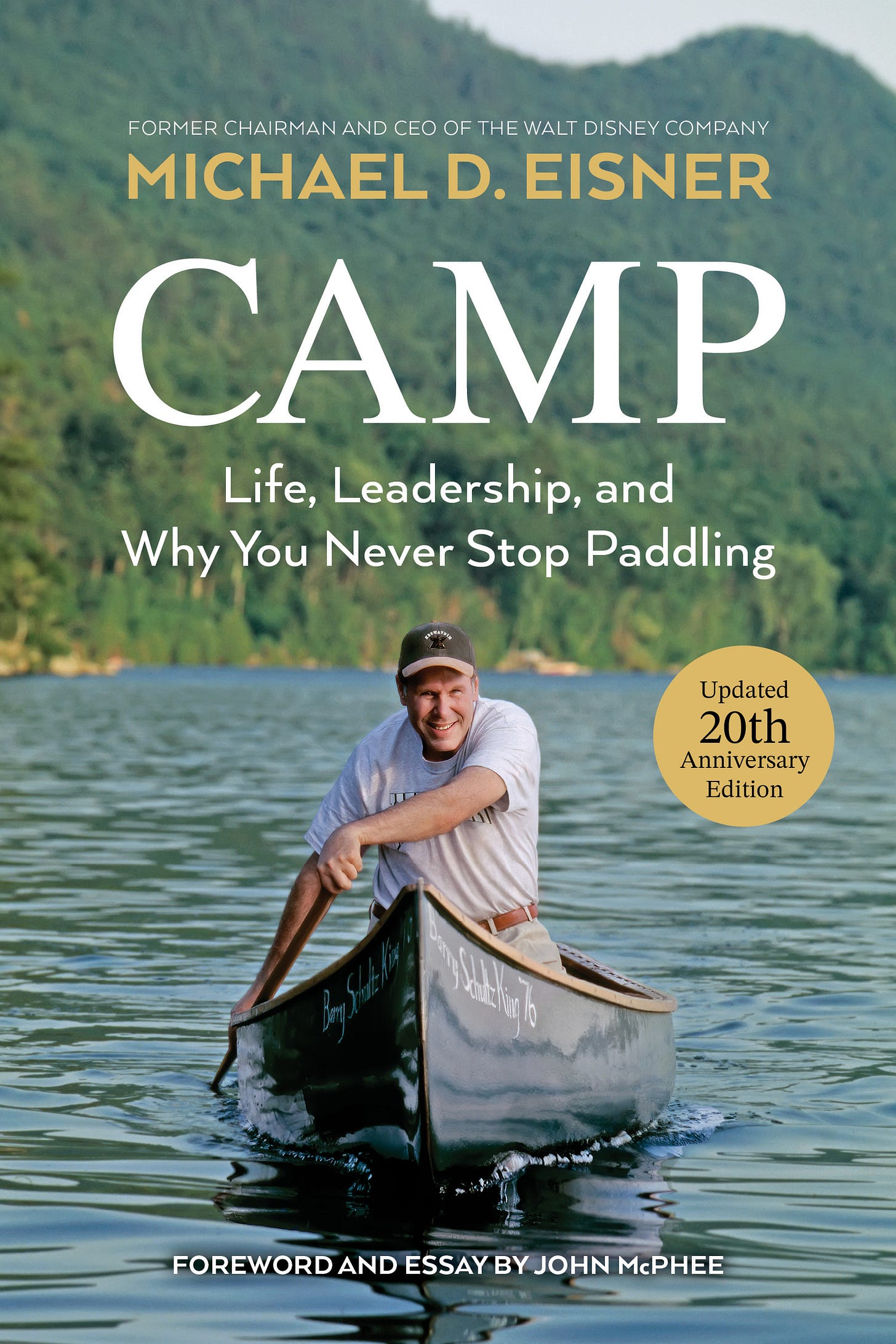

It’s a lifelong passion that runs deep enough to warrant a book. So in 2005, he penned the aptly-titled Camp, a slim tome chronicling the lore of his childhood sleepaway camp, Keewaydin, and its beloved longtime director, Alfred "Waboos" Hare. Four generations of Eisners have sat around Keewaydin campfires, a family tradition now stretching 100 years. And last month, Hyperion Avenue released an updated, 20th anniversary edition of Camp, an excellent gift for Father’s Day.

When he’s not writing about summer camp, Eisner is busy overseeing The Tornante Company, his investment firm, and running Portsmouth Football Club in England. It’s going pretty well: this year, the club clinched survival in the Championship League. He bought the franchise back in 2017, before many of his Hollywood neighbors joined him across the pond in English football ownership.

He’s one of the smartest minds in media and sports. So I rang up Eisner to talk Keewaydin, what it’s been like owning Portsmouth, and whether media and tech giants might follow his Disney strategy and purchase teams of their own.

How did a speech at the American Camp Association turn into Camp, your book?

I was at a Knicks game, and this guy came up to me and asked me at halftime if I would speak at that conference. And I said yes.

Now, my knee-jerk reaction when I’m asked to do something out-of-the-blue is no. I’ve learned that when you say yes, you don’t really think about it—it comes up in six months, and then you wonder how you ever said yes. But I did say yes.

And this friend of mine, John Angelo, said to me, “I thought you only spoke at colleges in which you wanted to get your children into.” Well, that generally could be true—not always. I had to speak at a lot of occasions for Disney.

But I said yes here because it was camp. And I had never thought about it—the effect it had on me.

And I then did do the speech. I’ve given a lot of speeches. These people were all camp-type people, and they went pretty nuts over the speech. I’m not used to standing ovations, to say the least—but this was one that they got it.

And I guess, based on that—I don’t remember who recommended writing a book about it—but out of that came, “Yeah, maybe I should write a book.”

Tell me about the ‘camp test’ with your wife?

So I did two things. One was to go to a baseball game to see if we were compatible with sports, like Barry Levinson’s movie Diner. I watched the game. She did the crossword puzzle the entire game. So she failed that. By the way, I’m still married to the same woman.

And the other was taking a trip into the Adirondacks, going back to Camp Keewaydin, getting all the equipment—the backpacks and the sleeping bags and the reflector ovens—and ending up in a very difficult situation with a bear for about 15 hours, where I was somewhat petrified, but hid it. The two people we met on the trail were completely petrified. And the one that stayed up was Jane. She figured out how to not have the bear eat us—all by keeping the fire going and banging the pots and pans—and then after staying up all night keeping the bear at bay, she walked out with me, Jane carrying 30 pounds, complaining maybe just a little.

I don’t know whether I passed the test or she passed the test, but we’re still together 58 years later.

There were a handful of Disney movies in the 1990s situated at sleepaway camps. Coincidence?

I always liked the idea of films about camps. I just can’t remember all the ones—whether television or movies—but the one that was of a high quality, that wasn’t exploitative in my opinion, was Meatballs, Ivan Reitman’s film, which he made in Canada, which we picked up.

We made others. And yes, the one great thing about the entertainment business is you can have a fairly normal, yet exciting life, like most people one way or another, you know, with kids and everything—and out of that comes movies.

I mean, obviously, we make most movies not about my own experience, but what makes movies particularly interesting to me—or books particularly interesting—is if you read a book and you see in a character— like in Catcher in the Rye—someone who is either you or a professor, and then you make a movie, Dead Poets Society being an example, which came out of two things for me, as I read the proposed script.

One was, when you went up to the dining hall at Keewaydin, there were tons of pictures—since the camp is 120 years old—from the ’30s and the ’20s, including my father. And all these pictures—and you look at them—and they’re all 10 years old, 16 years old, 18 years old—and you’re mesmerized by that. You see a picture of your father, you know, in the Cascades—which is a stream in the mountain—swimming, and then you see all these people later. It’s like, ‘Oh my god, this is history and tradition.’ And then you put that together with other experiences—I had a professor who played the trumpet, an English professor who stood on the table, doing all of the things we saw in Dead Poets Society.

So if you live a life and remember the highs and lows—which everybody has—and then you see the scripts that have them, about camp or whatever—especially if you were part of the Baby Boom generation, where your audience was kind of the same age as you were, which is now no longer the case—camp is part of that.

Before Ryan Reynolds bought into football with Wrexham, you purchased the English club Portsmouth. What drew you to English soccer and Portsmouth in particular?

Sports seemed to me the one thing that was demand viewing on television—and maybe the only thing that was appointment viewing, as the media grew into streaming, after cable and DVDs and all that. When I was at ABC, or even at Paramount, there were three networks. And then later there were cable channels. So there was a lot of appointment viewing at certain times, whether it's Happy Days or All in the Family, whatever, or movies or daytime soap operas or whatever. Those days are gone.

The only thing that is viewing by demand, by time period—Saturday at seven o'clock—is sports. So I thought that owning a sports team that had seen better days and you could grow it into something that recaptured its glory, which is what I like to do in media—whether it was ABC, Paramount, or Disney—that is to say, something that needs work, would be a good thing.

And we looked all over the world, and we decided on the English football pyramid. And we looked at a lot of clubs there, and we came across the island of Portsmouth, the naval city, with its rich history and ties to Henry the Eighth, and D Day, and a very emotional fan base. It just seemed like the right investment, in that year, 2017.

What I didn't want to do—which Ryan Reynolds did really well—is I didn't want to be an American Hollywood executive filming myself or filming the growth of Portsmouth. We were, in fact, the Wrexham story earlier, and we're one of the first Americans to own a team in the UK, but I felt that would be inappropriate for our fans. We wanted to be seen as series football owners.

Ryan Reynolds was smarter—maybe a little later. He's a movie star, which helped. Next year we'll play Wrexham twice in the Championship. We’ll play Birmingham, which has Tom Brady as an owner. We’ll play Southampton twice, which is a really historic rivalry with Portsmouth.

So all's well that is going well. We didn't get relegated for both men and women, which was amazing, because the women had an outstanding last six or seven games—as did the men. Frankly, this season was like a Disney story.

Before Portsmouth, you were involved in sports via Disney’s ownership of the Angels and Ducks. What was the best part about owning those franchises?

Our concept when Barry Diller and I came together within months in the ’60s was that ABC was fourth among three, and we had no money and we had no credibility. And so we went for young, up-and-coming stars, and we followed that together at Paramount. And people like John Travolta, Richard Gere, et cetera, came out of that. And in both places, we became number one—Paramount and at ABC—with many shows that were, I wouldn't say inexpensive, they were competitive, but they were original and new and had no stars and young directors.

And then Disney was similar. We made movies and television shows. Our negative cost was the lowest in the MPA companies, and we were number one or two every year.

So when we got the Angels—which we did as a favor to Anaheim, because Gene Autry’s widow was threatening to move them away from Anaheim—we took that same philosophy of young players that we hopefully found, and we won the World Series, which Gene Autry had never done and they haven't done since.

And on the Ducks—we started the Ducks. Again, everybody thinks we started the Ducks because two of my three sons played hockey, but that's ridiculous. We did it because we had a big relationship with Anaheim because of Disneyland; and they needed it, because they built an arena that had nothing in it. We named it The Pond, and again, they won the Stanley Cup.

So our strategy in Portsmouth is the same strategy, which is: we want to do it right. So it's all about young players some of which aren't from England, to the extent that we can get them. And next summer—next year—we're going to look for a player from the U.S. to enhance our U.S. appeal and find a great player or two..

So that's our strategy. Now, is it going to work again? I don't know, because most of our competitors want to get right to the Premier League, and they're paying fortunes for players. And that also may work, but I don’t believe it’s sustainable.

Sports is so integral to the future of media. As leagues embrace corporate ownership again, do you think media or tech companies will buy into franchises?

No, no, I’ll tell you why.

We bought the Angels, and we started the Ducks solely because of our relationship in Anaheim. One, because they were going to move the Angels, as I said, and the other because they built an arena and then found out they had no teams. That was the reason—because we were also working on a second park in Anaheim, where the city was putting in massive infrastructure so we could do it.

So it was, I would say, a favor and also a relationship issue that gave us some reward for doing that.

And here’s the bottom line of a media company—or any public company—owning a sports franchise: most of them lose money. And the way owners get out eventually is the equity increase. There are a lot of losses on the way.

So for a public company to absorb those losses every year, you make the shareholders angry. You’re spending a lot of money, so the fans love you. If you make the shareholders happy, the fans are going to hate you because you’re not spending the money on some fabulous Japanese pitcher or hitter.

So the bottom line is: you cannot win as a public company. You either make the fans happy by overspending, or you make the shareholders happy by not overspending.

So we sold the Ducks and the Angels eventually because of that dilemma. Who do you want to antagonize—your shareholders or your fans? That’s kind of the bottom line.

And one of the reasons I don’t have investors in Portsmouth is I really feel a fiduciary responsibility to a partner, and I don’t want a partner that I have to say, “Spend an extra Y to move up in the table, but you’re going to have to put in some more money.”

In sports, it’s a real dilemma.